Women Mobilizing Memory (2019)

with Maria Jose Contreras, Jean Howard, Marianne Hirsch, Banu Karaca, and Alisa Solomon

Women Mobilizing Memory, a transnational exploration of the intersection of feminism, history, and memory, shows how the recollection of violent histories can generate possibilities for progressive futures. Questioning the politics of memory-making in relation to experiences of vulnerability and violence, this wide-ranging collection asks: How can memories of violence and its afterlives be mobilized for change? What strategies can disrupt and counter public forgetting? What role do the arts play in addressing the erasure of past violence from current memory and in creating new visions for future generations?

Women Mobilizing Memory emerges from a multiyear feminist collaboration bringing together an interdisciplinary group of scholars, artists, and activists from Chile, Turkey, and the United States. The essays in this book assemble and discuss a deep archive of works that activate memory across a variety of protest cultures, ranging from seemingly minor acts of defiance to broader resistance movements. The memory practices it highlights constitute acts of repair that demand justice but do not aim at restitution. They invite the creation of alternative histories that can reconfigure painful pasts and presents. Giving voice to silenced memories and reclaiming collective memories that have been misrepresented in official narratives, Women Mobilizing Memory offers an alternative to more monumental commemorative practices. It models a new direction for memory studies and testifies to a continuing hope for an alternative future.

This volume confirms a shift of paradigm in the field of memory studies, linking it now to the mobilizing force of historical imagination. Without minimizing the devastating effects of violence and destruction, these authors demonstrate that the past is an archive of unlived possibilities and unpursued futures. Time shifts as one reads each of these pieces, grounded in an uncertain aftermath of dictatorship and war, or continuing colonization. They tell histories that release ways of imagining what could have been and even what should have been, experimenting with tense to open political pathways and affirmative politics from the sustained and discerning reflection on abysmal loss. Opposed to revisionism, these authors probe more deeply into the past than positivist histories have ever done, following the flash of possibility into the future. A brilliant, timely, and singular volume. Judith Butler

This is more than an extraordinary book—it is a fascinating journey around the world. It links the North and Global South through Europe, Chile, Turkey, and the United States in the name of innovative feminist practices able to rethink, reframe, and give new insight into memories of a traumatic past and difficult present. Showing the limitations of institutionalized forms of memorialization, this work truly opens up new paths for alternative forms of knowledge and political resistance. Patrizia Violi

Reclaiming the word “mobilizing” from its militarized context, the authors of this book set an example of how transnational feminist scholarship can produce much-needed understanding of how memories of painful pasts can be interpreted beyond trauma in an empowering way, offering a livable vision of the future for all. Andrea Pető

Women Mobilizing Memory (eds. Ayşe Gül Altınay, Maria Jose Contreras, Jean Howard, Marianne Hirsch, Banu Karaca, and Alisa Solomon), New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

Gendered Wars, Gendered Memories: Feminist Conversations on War, Genocide and Political Violence (2016)

Gendered Wars, Gendered Memories: Feminist Conversations on War, Genocide and Political Violence (2016)

with Andrea Pető

The twentieth century has been a century of wars, genocides and violent political conflict; a century of militarization and massive destruction. It has simultaneously been a century of feminist creativity and struggle worldwide, witnessing fundamental changes in the conceptions and everyday practices of gender and sexuality. What are some of the connections between these two seemingly disparate characteristics of the past century? And how do collective memories figure into these connections? Exploring the ways in which wars and their memories are gendered, this book contributes to the feminist search for new words and new methods in understanding the intricacies of war and memory. From the Italian and Spanish Civil Wars to military regimes in Turkey and Greece, from the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust to the wars in Abhazia, East Asia, Iraq, Afghanistan, former Yugoslavia, Israel and Palestine, the chapters in this book address a rare selection of contexts and geographies from a wide range of disciplinary perspectives. In recent years, feminist scholarship has fundamentally changed the ways in which pasts, particularly violent pasts, have been conceptualized and narrated. Discussing the participation of women in war, sexual violence in times of conflict, the use of visual and dramatic representations in memory research, and the creative challenges to research and writing posed by feminist scholarship, Gendered Wars, Gendered Memories will appeal to scholars working at the intersection of military/war, memory, and gender studies, seeking to chart this emerging territory with ’feminist curiosity’.

For decades feminist historians have listened to stories of women narrating their experiences of war. This volume brilliantly shows us these narratives are part of a volatile memory, which forces us to reconsider any information that is narrated and to interrogate further meanings and possibilities. It is a major step in a field where truth has become a particular and subjective truth. Selma Leydesdorff

With international scope and scholarship, this volume documents – pointedly, painfully, perceptively – how modern war and genocide assault women and, at times, implicate them as perpetrators of atrocity. Never minimizing the wreckage, the contributors salvage what remains – archival records, crucial memories, insistent responses – the ingredients necessary to press men as well as women to advance the protest and resistance demanded by the book’s tormenting and unforgettable findings.’ John K. Roth, Claremont McKenna College, USA ’This original and moving book pushes forward our current thinking and existing debates on the gendered memories of war and violence. Covering a range of different case studies and empirical contexts, the contributions offer timely and cutting-edge insights, creative methodologies and compelling analyses. Nadje Al-Ali

In its transnational and interdisciplinary set of feminist engagements, this book fills a glaring gap in the study of how violent pasts are memorialized. It reorients the study of war, memory and gender by looking beyond lasting violence, to resistance, re-imagination and the future. Marianne Hirsch

Open Access: Introduction – Uncomfortable Connections: Gender, Memory, War by Ayşe Gül Altınay and Andrea Pető

European Journal of Women’s Studies Special Issue – Gendering Genocide (with Andrea Petö, 2015)

European Journal of Women’s Studies Special Issue – Gendering Genocide (with Andrea Petö, 2015)

“There’s a tremendous kind of hesitation in the scholarship on genocide to highlight gender because such a totalizing form of annihilation makes it very difficult to make differentiations among victims. And yet, once you raise the question of gender, your very terms of analysis are sharpened, certain structures of perpetration, of experience, memory and transmission come into sharper focus. (Marianne Hirsch, this issue)

One of the motivating factors behind this special issue has been the centennial of the genocide of the Ottoman Armenians in 1915–1916. The issue draws on this moment to reflect on the 20th century as a century of genocides and to look into the 21st century debates on the intersections of genocide and gender. How are genocides, as well as the politics and study of genocide, gendered? Where do we stand in the feminist theorizing of genocides and their legacies? What role does gender play in the international legal and political frameworks that have been formulated to prevent and punish genocidal acts? Where can we locate the gaps, silences and contradictions in the feminist studies of genocide, and what new directions promise new openings? Starting with our conversation with Marianne Hirsch, who has been a pioneering feminist theorist of genocides and their (post)memories, the contributions to this Special Issue address these questions, and more, from a wide range of disciplinary and theoretical vantage points. As we discuss below, whereas the contributions in the Articles section focus predominantly on the conceptualization, legalization, internationalization, as well as the (post)memories of sexual violence in relation to genocides and wars, the essays in the Open Forum explore other key issues that have come up in the feminist studies of genocide. From the ethics of knowledge production on the gendering of genocides, to the gaps and silences in the feminist literature and the (inter)national organizing around genocide, these essays engage in self-critical overviews, as well as pointing to future directions in research and debate on the intersections of gender and genocide. What all contributors seem to agree on is the need to complicate our understanding of what constitutes genocide; the (often gendered) dichotomy of perpetrator vs. victim; the binary, heteronormative understanding of gender; as well as the concept of ‘unsilencing’.” (from Ayşe Gül Altınay and Andrea Pető, “Introduction: Europe and the century of genocides: New directions in the feminist theorizing of genocide” European Journal of Women’s Studies, Gendering Genocide Special Issue, 22(4): 379-385).

New Perspectives on Turkey Special Dossier – “Gender, Ethnicity and the Nation-State” (with Hülya Adak, 2010)

New Perspectives on Turkey Special Dossier – “Gender, Ethnicity and the Nation-State” (with Hülya Adak, 2010)

Dedicated to the Memory of Dicle Koğacıoğlu (1972-2009)

“In May 2010, Sabancı University, the International Hrant Dink Foundation, and Anadolu Kültür co-organized the second Hrant Dink Memorial Workshop around the theme “Gender, Ethnicity, and the Nation-State: Anatolia and Its Neighboring Regions in the Twentieth Century.”1 Earlier versions of the articles published in the dossier of this issue of New Perspectives on Turkey were presented at this work- shop. Focusing on moments of transformation in gender and ethnic relations during both the construction of nation-states, as well as their transformation(s) during the twentieth century in Anatolia and its neighboring regions, the workshop brought together close to 200 people from eighteen countries, turning it into a three-day conference.2 Both the overwhelming interest in the workshop and the scope and quality of the presentations were testimony to the centrality of gender, ethnicity and the nation-state in contemporary academic debates in/ on this region.”

“Towards a different future: In one of the televised debates in which he participated, Hrant Dink defined discrimination based on gender and sexual orientation as a form of racism. In his dedicated struggle against all forms of discrimination, oppression, and exploitation, the crossroads between gender, sexual orientation, and ethnicity constituted spaces of critical and creative intervention to imagine a different future. Whether they engage in an open discussion of “a different future” (as does Avakian), or draw the contours of that future through their analysis, the contributions to this dossier chart creative paths for moving beyond the various methodological nationalisms, the normalization of gender roles, the silencing (or, conversely, naturalization) of ethnic iden- tifications, as well as the hetero-normativity in scholarship and politics alike—just like the legacy of Hrant Dink, whose memory and struggle has brought us together in the first place, and that of Dicle Koğacıoğlu, whose work on gender, ethnicity, and nationalism has been profoundly inspiring.”

(from Hülya Adak and Ayşe Gül Altınay, “Guest Editors’ Introduction: At the Crossroads of Gender and Ethnicity: Moving Beyond the National Imaginaire”Dossier on Gender, Ethnicity and the Nation-State, New Perspectives on Turkey 42 (Spring):9-30.)

Torunlar (2009)

Les Petits-Enfants (2011)

Torner (2011)

The Grandchildren (2014 & 2017)

with Fethiye Çetin

“This is not an easy book to read. The stories that follow were painful to tell, painful to hear, and painful to set down on paper. Only a few of the grandchildren we met were willing to share their stories in this volume. For those who agreed to do so, it was anything but easy, at least emotionally. And one had a change of heart very close to the time of publication. When this person informed us of her decision, we could hear deep fear and anxiety in her voice. Despite the fact that her story would remain anonymous, thus keeping her identity safe; this ‘grandchild’ had been too deeply marked by the conflicts she had witnessed in the first decades of her life, not to mention the forced migration of her family from their Kurdish hometown in the 1990s, and the struggle to make a new life elsewhere, for her fears and anxieties to abate. The suffering of her Armenian grandfather was not in the past; three generations later, it was still shaping her present and her future.

This is not a book about 1915 so much as a book about what Hrant Dink described as being ‘stuck in a well 1915 meters deep’. It is a book that traces the deep scars that people living in these lands today still carry from the humanitarian catastrophe of 1915 – and that finds them in the most unexpected places.

Almost a century later, what does it mean to be a grandchild of those who survived 1915? At least as important is to ask what happened next: what have these survivors had to endure, these grandchildren, parents and grandparents, their neighbors, and their friends? A hundred years on, why is it still so difficult, so painful, for grandmothers and grandfathers (or mothers and fathers, or any of us) to own up to our Armenian heritage? If we found a way to face up to this pain, and to this silence, would this free us to identify other silences, other sources of anguish, bringing them to the surface by putting them into words? And could this process help to assuage yet other pains and silences before they have a chance to fester?” (Ayşe Gül Altınay and Fethiye Çetin, Foreword to the English Edition, 2015)

“Despite the rapid rise in works being published on this subject, we still know very little about the converted Armenian women, men and children survivors, or the lives they went on to lead. Each of the 25 stories in this book opened up new doors for us. Each story we heard shocked us, teaching us new things, and leading us to ask new questions. Not one of the grandmothers and grandfathers named in these stories is still with us. Their lives brought them great pain and difficult choices, but they were also full of beautiful things they shared with those they loved. As their children and grandchildren told their stories, they spoke a great deal about how sad these grandparents were, and how silent, and how much they cried. As they told their stories, they too would often fall silent, feel pain, and even cry. We often cried together. During our interviews, one of the subjects that the children and grandchildren spoke about most – what made them think most deeply, what made them cry – was the complex layering of silence in their lives. The impossibility of finding a way to open the subject, the years of hiding it like a ‘family secret’, the fear that others might discover the secret, and, because this secret could not be shared, all these other things that could not be shared either…

The 25 stories in this book invite academics, independent researchers, authors, journalists, and each and every one of us to begin peeling back the many layers of silence discussed here by allowing ourselves to be curious and to ask ourselves and each other questions, instead of relegating those questions about history to the archives. An important component of this invitation is not to remain blind to the many other forms of suffering taking place today, as we delve into the past. In other words, they warn us against creating new silences, while breaking the silences of the past… As we read these stories, there are several questions we can all ask ourselves: If these children and grandchildren were standing before me now, what would I want to say to them? If I were one of them, what would I want others to say to me? What is my relation to the stories being shared here? How – as an academic, a writer, a journalist, a politician, a friend, a citizen – might I have contributed to the silence that has brought them such hardship? What sorts of silences am I myself suffering from? What other silences might I still be complicit in? What sort of privileges might some of these silences be providing me and at what price to others? And, perhaps most importantly, how can we pull away all these layers of silence, to heal ourselves, and each other?” (Ayşe Gül Altınay, “Afterword: UnravelingLayers of Silencing:

Where are the Converted Armenians?” in The Grandchildren)

Torunlar, İstanbul: Metis (with Fethiye Çetin, 2nd edition February 2010)

French: Les Petits-enfants, trans. Célin Vuraler, Arles: Actes Sud, 2011.

Armenian: Torner, trans. Lilit Gasparyan and Tigran Mets Hratarakchatun, Yerevan: Targqnutyun, 2011.

Türkiye’de Kadına Yönelik Şiddet (2007)

Violence Against Women in Turkey (2009)

with Yeşim Arat

“To trace women’s experience of and the feminist struggle against domes- tic violence by male spouses (the major form of gender-based violence ad- dressed by second-wave feminism in Turkey) from the late 1980s till today, we conducted an 18-month research project titled “Domestic Violence and the Struggle against It,” supported by TÜBİTAK (The Scientific and Techno- logical Research Council of Turkey). The project had two legs. First, based on in-depth interviews and focus group discussions, our research aimed at analyzing the mechanisms of empowerment, support, and awareness-raising developed by women’s organizations at both the national and the local level, and to discuss the factors that contribute to the success, as well as the chal-lenges and limitations of this organizing. Between February 2006 and June 2007, we interviewed more than 150 feminist activists from close to 50 organizations in 27 cities.

Second, we conducted a nationwide representative survey in spring 2007. Based on face-to-face interviews with 1,800 ever-married women from a to- tal of 56 provinces5, this survey was the second nationwide study on domes- tic violence (first being a 1993 survey). The questionnaire for the survey was developed after a year of in-depth interviews with activists in women’s organizations and with the feedback of more than a dozen academics and activists specializing in this field. Besides this participatory process of survey preparation, an indispensable component of the feminist methodology we tried to adopt was approaching the women to be interviewed for the survey as “subjects” in the debate on domestic violence. This required a move away from a focus on women’s “experience” of violence towards a questionnaire design that would help bring out their views on the background, legitimacy, prevention, and penalization of spousal violence. As we discuss in greater detail in the coming pages, the survey ended up having three parts: 1) what women think about domestic violence by their spouses (background and legitimacy), 2) women’s experience of domestic violence by their spouse, and 3) women’s views on prevention and penalization (with a particular emphasis on the role of the state).”

“In the Turkish debates, four key findings of our research have received particular attention. First, the combined outcome of two of the questions in the survey have revealed a growing awareness of and decreasing toler- ance towards domestic violence by women. Nine out of ten women agreed with the statement that “wife-beating” was never justifiable (as opposed to the statement that under certain circumstances beating could be justified) and nine out of ten women said “yes” to the question of whether the courts should “penalize” the men who exercise violence against their wives. These results (reinforced by responses to other questions) suggested that women did not regard domestic violence as a “private affair” that needs to be solved “within the family.” Since this goes against the findings of earlier surveys and against popular assumptions of women’s response to violence, there was special interest expressed in the media, as well as by activists, lawyers, psychologists, doctors, and politicians in this finding. Many people, including us, interpreted this as an encouraging outcome of 20 years of successful struggle by feminists. This finding revealed that the feminist struggle against domestic violence has not only been successful at changing the terms of the debate in the media or introducing new laws and state policies, but that the main message had reached, and had been internalized by the great majority of the women in Turkey.

The second key finding that attracted particular attention has been the increasing risk of physical violence for women who make more money than their husbands. Whereas the national percentage of women participating in the survey who have ever experienced physical violence from their husbands turned out to be 35 %, this percentage climbed up to 63 % for the women who contributed more income to the household economy than their husbands. Those who had equal incomes seemed to bear the lowest risk (20 %). This finding challenged the popular assumption that women endured domestic violence because of economic dependency and reinforced the feminist emphasis on the need to understand the gendered power relations behind domestic violence.

Thirdly, there was significant attention paid in the debates to the “silence” of the women experiencing male partner violence. The survey results suggested that as many as 49 % of the women who had been physically abused by their male partners nationwide had not shared this experience with anyone else before sharing it with our interviewers. While this finding was a positive indication of the rapport established between our interviewers and the women participating in the survey (since they were able to share their experience of violence with the interviewers), it was a striking sign of women’s solitude when faced with violence.

Finally, the finding about the lack of significant statistical difference be- tween the East and the rest of the country regarding both the rates of violence and women’s attitudes towards violence (despite a huge gap in terms of income and education levels) 6 attracted media and scholarly attention. Combined with the finding about the increased risk of violence among women with higher income than their husbands, this lack of significant statistical difference between the East and the rest of the country challenged the popular understanding that “it is the Eastern women who are abused; the women in Western Turkey are more liberated.” While the scope of this national sur- vey is not enough to engage in a detailed analysis of all aspects of gender- based violence experienced by women across regions, nevertheless, our limited findings are enough to question the myth about gender-based violence being ‘an Eastern issue’ in Turkey.”

from Ayşe Gül Altınay and Yeşim Arat, “Preface to the English Edition” (January 2009)

- The more comprehensive Turkish edition Türkiye’de Kadına Yönelik Şiddet (İstanbul: Punto, 2007) received the 2008 PEN Duygu Asena Award

İşte böyle güzelim… (2008)

Hülya Adak, Ayşe Gül Altınay, Nilgün Bayraktar, Esin Düzel

So ist das, meine Schöne

Hülya Adak, Ayşe Gül Altınay, Nilgün Bayraktar, Esin Düzel

Translated from Turkish by Constanze Lesch.

Ebru: Reflections on Cultural Diversity in Turkey (2007)

by Attila Durak, edited by Ayşe Gül Altınay

excerpt from Ayşe Gül Altınay, “Ebru: Reflections on Water” in Ebru: Reflections on Cultural Diversity in Turkey (Attila Durak, ed. Ayşe Gül Altınay, Metis 2007)

The Myth of the Military-Nation: Militarism, Gender and Education in Turkey (2004)

The Myth of the Military-Nation: Militarism, Gender and Education in Turkey (2004)

The Myth of the Military-Nation is a precious gift to those many of us who want to understand the cultural processes through which manhood and national belonging come to be inseparable from soldiering – and the courage and cost involved in reaching for an unmilitarized way of being. Cynthia Cockburn

With all the news about Turkish politics due to the Cyprus, Iraq and EU debates, now is exactly the time for all of us to read this smart feminist investigation of the Turkish political interplay between masculinity, men, statist nationalism and soldiering. Altinay is one of the most insightful political anthropologists I know. Cynthia Enloe

This is a work which contributes essential substance to modern history, peace and security studies, gender studies and to the theory and practice of education. It should be read by every educator concerned by the disservice to critical learning done by the militarization of education. Betty A. Reardon

The Myth of the Military Nation is exemplary of the politically engaged scholarship that has acquired momentum with a new generation of Turkish scholars committed to exposing national myths to overcome past and present injustices in Turkish society. Altinay ably combines ethnography with rich and historically informed scholarship to demonstrate the historical production of the idea of a military-nation as a foundational myth of Turkish nationalism, and offers a critique of the institutional and ideological sources of its hegemony that is all the more effective for its heart-felt but subdued tone. Arif Dirlik

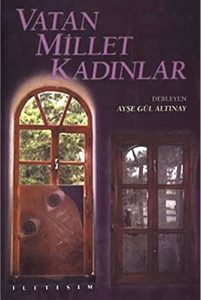

Vatan Millet Kadınlar (2000, 6th edition 2016)

Vatan Millet Kadınlar (2000, 6th edition 2016)

One of the first edited volumes that analyzes the interface of nationalism and militarism from an intersectional feminist perspective, Vatan Millet Kadınlar (Homeland Nation Women) brings the translated works of international feminist scholars like Cynthia Enloe, Afsaneh Najmabadi, Sylvia Walby, Rubina Saigol, Joane Nagel and Partha Chatterjee in conversation with the emerging (emerging in 2010, by now widespread and vibrant!) feminist scholarship on nationalism and militarism in Turkey by Esra Özyürek, Meltem Ağduk, Selda Şerifsoy, Lale Yalçın-Heckmann and Pauline van Gelder. The introduction inquires about the diverse role women have played in the recent history of Turkey in relation to deeply gendered and militarized nationalist projects, most prominently in the context of Turkish nationalism. From feminist activists who challenged the patriarchy of state nationalism and built alliances around “sisterhood” to prominent women like Sabiha Gökçen who became enthusiastic actors of militarized statehood, from devout Muslim women like Konca Kuriş who faced discrimination and violence for their gender politics, to Kurdish women speaking about their experience of racism and discrimination within the feminist movement, the book explores the diverse ways in which gendered nationalism and militarism have shaped the past century of life and politics, including feminist politics, in Turkey and beyond.

The editorial process, which was an amazing collective effort, supported generously by the editors, writers and translators of İletişim, as well as by the scholars who came together to discuss their articles – based on original, cutting-edge research – with one another and with me. To all the authors who shared their insightful research into this uncharted and politically perilous territory, the international scholars who gave us permission to publish their works in Turkish (in most cases, for the first time), to Tansel Demirel, Asena Günal, Elçin Gen and Aksu Bora for their encouraging companionship through the process, as well as their beautiful translations and editorial support. It was first in this book that I wrote about the story of Sabiha Gökçen, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s adopted daughter and the world’s first woman combat pilot. I continued to explore the depths and fascinating layers of her story in my PhD dissertation, in The Myth of the Military-Nation (2004), and in numerous articles and essays since then. A year after the book was published, I was taking the Sabiha Gökçen Airport exit everyday to go to Sabancı University campus, my new academic home. I still take that exit and Sabiha Gökçen’s story continues to unfold in the most unexpected – at times unsettling and heartbreaking – ways…

The photograph and art work on the beautiful cover of Vatan Millet Kadınlar came from a feminist artist, Muteber Yüğnük, who generously offered this capturing image to accompany our conversations on the generative thresholds between dark and light, war and peace, inside and outside, the personal and the political, the self and the other. No doubt that Muteber and her fascinating art installation has invited many readers inside, contributing to the book being in its 6th edition 🙂

Ayşe Gül Altınay

Ayşe Gül Altınay